The words “core” and “abs” are often interchangeable in casual workout conversations, but the core is more complex than that coveted six pack. Training both the deep and superficial core muscles protects the spine, increases stability and mobility in joints, and safeguards against injury.

The superficial abdominals that show up when belly fat disappears are just a fraction of the big picture. Having a strong, stable core extends beyond what is seen on the surface. In other words, a ripped stomach does not equal strength and stability. Learning how to tap into the inner core will not only deliver beach-ready abs, but will also increase strength and mobility. Let’s take a look at what makes up the core and how it works.

The Core Make Up

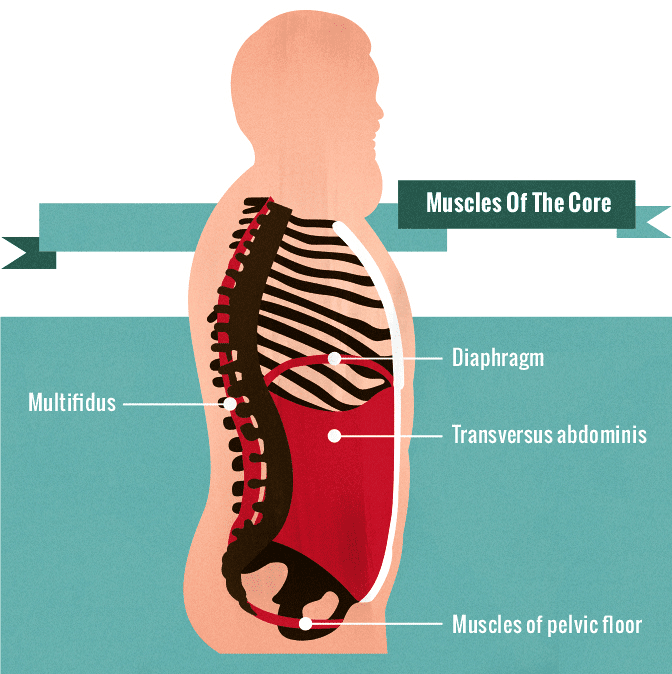

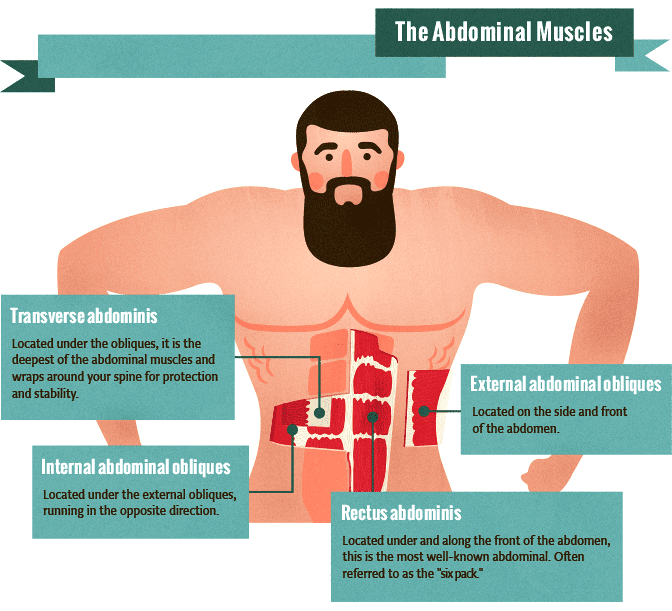

Though different practitioners have various definitions for the core, the term “core” is used to describe the muscles, bones, and tissue from the sternum to the hips. Think of the core as a cylinder with the diaphragm at the top, the pelvic floor at the bottom, and the walls as the deep torso muscles (transverse abdominis, multifidus, internal obliques) as well as the superficial torso muscles (rectus abdominis, external obliques). The core also includes the hips, SI joint, psoas, pelvis, and lumbar spine.

The core is often thought of as a prime mover for trunk flexion and extension –basically bending forward and leaning back. In turn, most core training revolves around movement, including crunches and back extension (which isn’t a back exercise, but a glutes exercise). But in order to achieve optimal core strength and stability, it’s important to think beyond squeezing the abs.

The core is responsible for proper breathing, maintaining posture, joint stabilization (including the spine), energy absorption and transfer, and urinary and fecal continence. The inner core must be balanced with the outer core for all of these awesome functions to take place – hence the need to think beyond the abs.

To gain a better understand of what the core looks like and how it functions, here is a breakdown of each muscle.

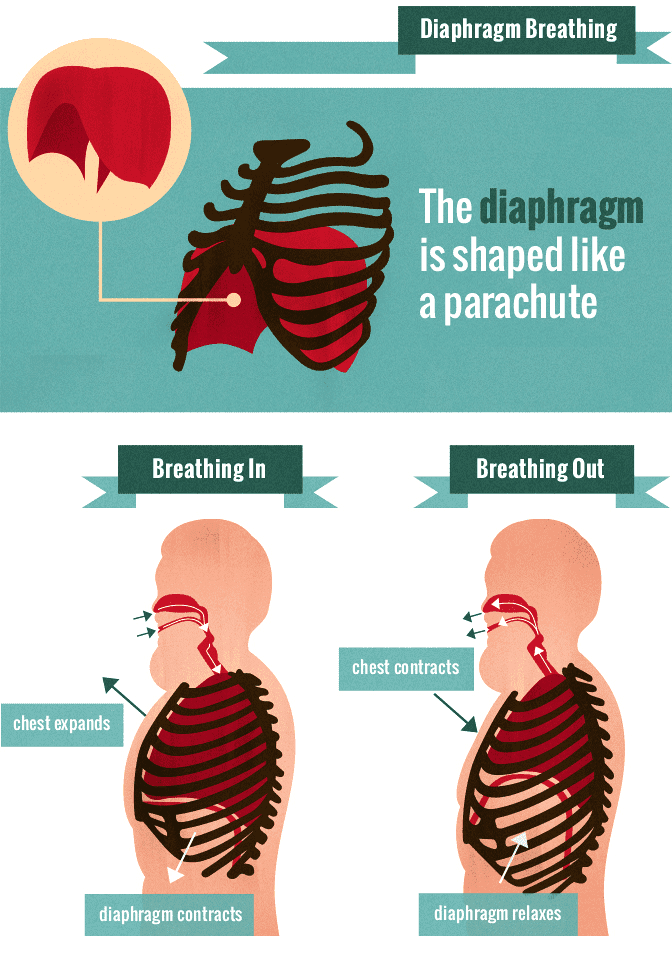

The pelvic floor: The pelvic floor sits like a cradle inside the bony pelvis. These muscles support pelvic organs, promote waste continence, aid in sexual function, act as lymphatic pumps, and stabilize connecting joints. The pelvic floor works in conjunction with the diaphragm to regulate breathing and stabilize joints. During an inhale, the diaphragm pushes down, putting pressure on the abdominal wall. The pelvic floor accepts this pressure and descends slightly due to its elasticity. During an exhale, the pelvic floor recoils and the diaphragm ascends.

The diaphragm: The diaphragm is an umbrella-shaped muscle located at the base of the lungs, below the sternum. Music teachers stress the importance of the diaphragm because it helps regulate proper breathing patterns. The diaphragm has to activate before the abdominal wall during regular breathing as well as various movement patterns. Mix this up, and the diaphragm cannot descend properly, which decreases spinal stability. Intra-abdominal pressure is created when you activate your diaphragm, pelvic floor, and abdominal wall together. This is often referred to as bracing during exercise. This keeps your spine and pelvis aligned during planks and push-ups, and protects your spine during deadlifts and squats.

Practice: Diaphragmatic breathing or belly breathing strengthens the diaphragm and abdominal wall and also works as a great stress reliever. Here’s how to do it.

- Lie on your back on a mat or bed with a pillow supporting your knees and head. Place the left hand on your chest near your clavicle and the right hand below your sternum where your diaphragm is located.

- Breathe in through your nose starting your breath at your diaphragm. Fill your belly with air so that the right hand is moving upward. The left hand should remain completely still.

- Exhale through your mouth, and, while keeping your abdominal muscles tight, pull your belly button toward the spine so that the abdominals fall inward and the right hand lowers. The left hand should remain still.

- Practice this for 10 belly breaths in and out.

Multifidus: The multifidus is a series of superficial and deep muscles attached to the spine that keeps it straight and stable. These muscles activate before back extension and rotation to protect the spine from injury.

Transverse Abdominis: The transverse abdominis (TA) is a stabilizing muscle group deep in the abdominal wall. Rather than moving the body like the rectus abdominis and obliques, the TA compresses and supports the abdominal cavity and spine like a corset. The TA is a postural muscle group, so it should be trained differently than the movers. This is likely the most overlooked muscle group in the core, and often the rectus abdominis is far stronger than the TA.

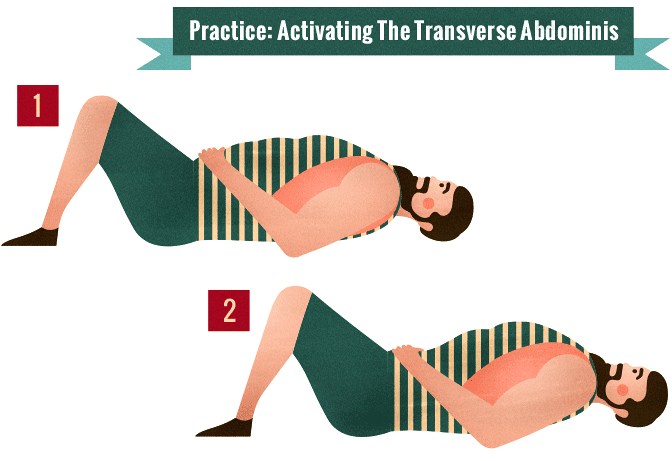

It’s important to start all postural exercises by activating the TA. This is easier said than done, so here is a good activation exercise to perform. This will teach you how to activate your TA prior to exercises that require spinal stabilization like planks, push-ups, bicycle, pull-ups, etc.

Abdominal Draw-In

- Lie face-up with a pillow supporting the head. Bend the knees, placing feet flat on the floor.

- Place a rolled up towel or tennis ball between the knees.

- Slightly roll the hips up to bring your low back toward the floor and align the pubic bone with the pelvis. Squeeze the towel between the knees and draw the abdominals in so that the navel pulls back toward the spine. Do this without moving the chest or crunching the rectus abdominis.

- Perform each rep for five seconds, but do not hold your breath.

- Repeat for five repetitions in three sets.

Rectus Abdominis: These long, flat muscles extend vertically along the length of the abdomen and are what is known as the six-pack. These muscles flex the torso and spine by pulling the rib cage closer together. Crunches work the rectus abdominis, but too many crunches and not enough deep core activation can lead to a weak TA.

External and Internal Obliques: These broad, superficial muscles lie on the lateral sides of the abdomen outside of the rectus abdominis. When contracted, these muscles perform several different movements including lateral flexion and trunk rotation. Internal obliques are positioned between the external obliques and the TA. When acting together, both sides flex the vertebral column, bringing the pubis toward the breastbone. Separately, when they contract it brings the vertebral column to the side or rotates it.

Make It All Work Together

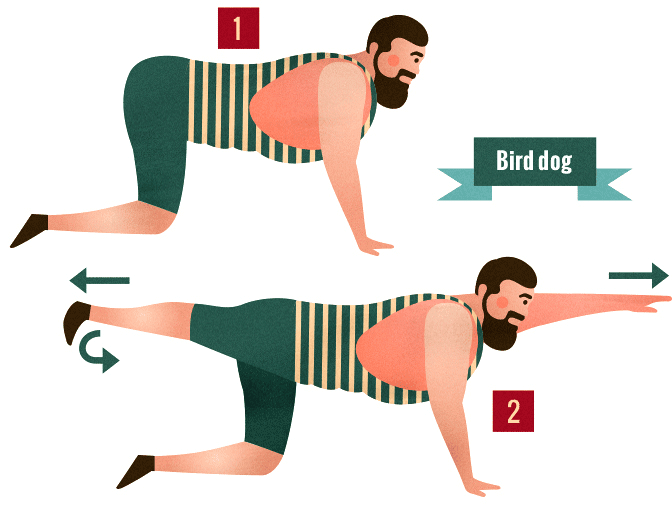

Bird dog

- Rest on all fours: Place hands under shoulders and align the knees under the hips.

- Draw the abdominals in toward your spine to activate TA.

- Extend the right arm and left leg until they create a straight line with your torso. Keep the abdominals drawn in and contract the glutes at full extension.

- Lower arm and leg back down and repeat for 10 reps on the same side. Switch sides and repeat for 10 more reps.15

Tips:

- Avoid allowing the spine to arch and the abdominals to move toward the floor as the hip extends.

- Extend the leg straight back, keeping it in line with the hip. Do not allow the working leg to move outward, away from the stationary leg.

- If it is difficult to move the arm and leg simultaneously, switch to just the arm, then just the leg, then try for both as you progress.

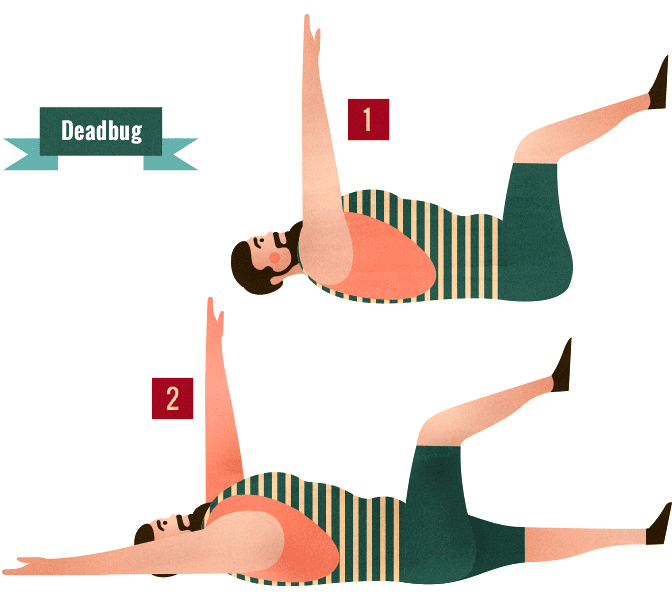

Deadbug

- Lie face-up with feet on the floor. Roll the hips up to align the pubic bone with the pelvis and draw the belly button toward the spine.

- Place both arms up with fingertips toward the ceiling and both legs up with bent knees.

- Move the right leg and left arm out to full extension so that the elbow is by the ear and the leg hovers above the floor. Return to starting position and repeat on the other side for a total of 10 repetitions on each side.16

Tips:

- As the arm and leg extend, do not allow the chest to rise and arch the back. Maintain a neutral spine and keep the core engaged.

- If this is not possible, stop the movement at the point before the chest begins to rise and the back begins to arch. Over time, work to increase this range of motion to full extension.

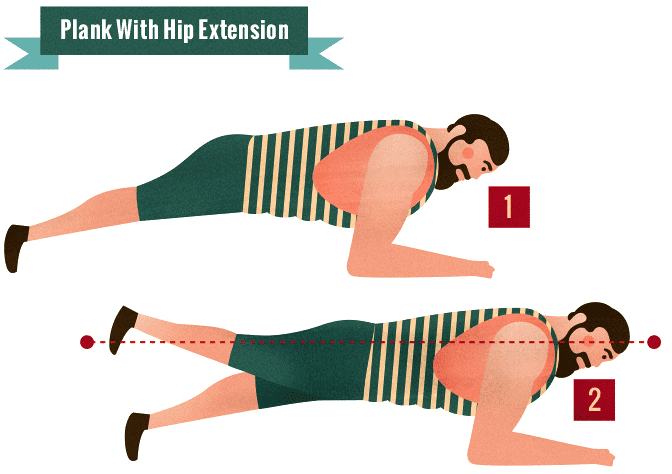

Plank From Elbows With Hip Extension

- Lie on a mat face down, rising up onto your forearms and toes.

- Maintain abdominal draw-in and contract the glutes so that the pelvis aligns with the ribs and pubic bone.

- Extend the right leg upward toward the ceiling, keeping a contraction in the glutes. Hold for two seconds and repeat for a total of 10 times.

- Perform the same movement on the left side.

Tips:

- Maintain the abdominal draw-in and glutes contraction throughout the duration of the exercise. If form breaks, reset before continuing.

- If hip extension is too difficult, perform front planks only.

Plank From Side With Hip Abduction

- Lie on the right side with the elbow under the shoulder. Rise up so the body is resting on the forearm and foot.

- Contract the obliques and raise the top leg toward the ceiling. Lower the leg and repeat ten times.

- Switch to the left side and repeat.

Tips:

- Keep the obliques contracted so the body remains aligned and the spine neutral.

Elbow pain during this exercise can result from not positioning the arm directly under the shoulder.

WRITTEN BY

Kellie started her career as a fitness writer in 2009 with a blog. That has led to co-authoring a women’s strength training book called Strong Curves. She currently attends graduate school at The George Washington University and lives with her husband and two children.