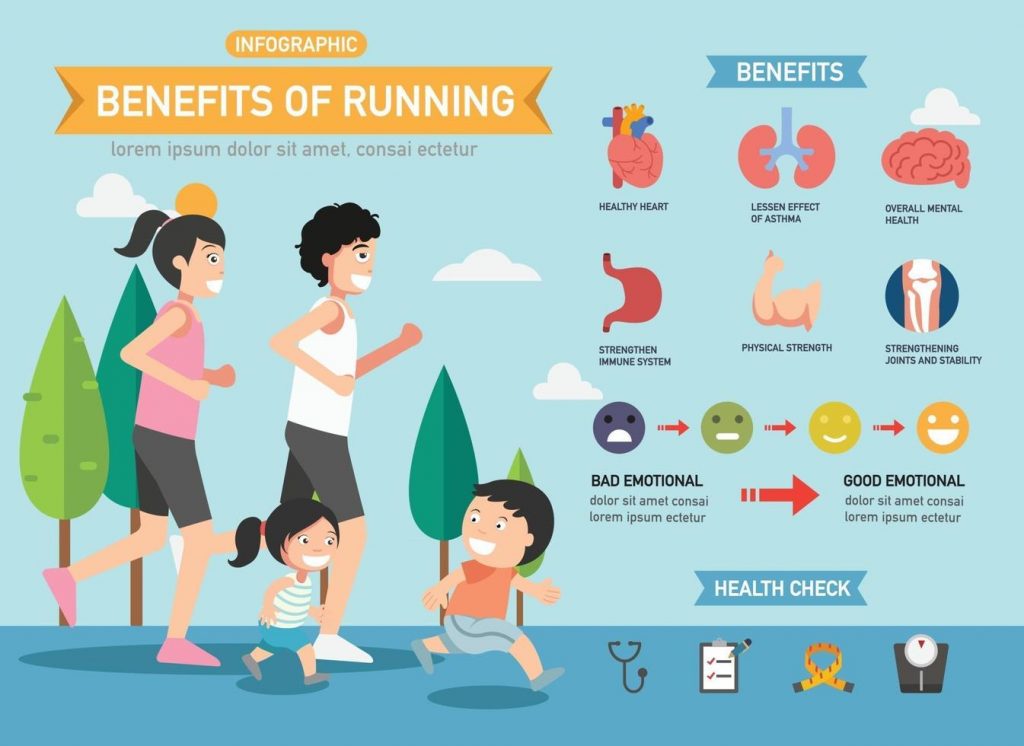

The benefits of running on cardiovascular health have become a cornerstone of well-established research, painting a compelling portrait of the advantages that runners enjoy. Beyond the evident physical prowess, individuals who embrace the rhythm of running often find themselves on a path toward longer lifespans and reduced mortality rates. This journey, however, extends far beyond the cardiovascular realm.

Delving into the realms of cardiac well-being, runners exhibit lower rates of cardiac death, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and stroke. The perks continue with decreased risks of obesity and diabetes, coupled with enhanced lipid profiles that set them apart from their non-running counterparts. Even when factoring in the generally healthier lifestyles of runners, encompassing superior diets and lower alcohol consumption, the statistics speak volumes about the protective influence of running on our hearts.

Yet, the narrative of the benefits of running unfolds on a broader canvas. Runners not only defy cardiac odds but also demonstrate diminished rates of depression, fostering a profound sense of community within the local running fraternity. The satisfaction derived from achieving athletic milestones intertwines seamlessly with the opportunity to contribute to charitable causes through these accomplishments.

Cost-effective and accessible, running requires minimal specialized equipment, making it an inclusive endeavor for individuals across diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. The health dividends, remarkably, reveal themselves even with modest amounts of light jogging per week, making running an attractive proposition for those seeking an approachable yet impactful fitness routine.

However, as we celebrate the virtues of running, a subtle undercurrent of inquiry arises – is all running universally beneficial? Recent studies have introduced a nuanced perspective, suggesting potential drawbacks associated with prolonged endurance training. This prompts a crucial question: is there a threshold at which the scales tip, and the health risks of running outweigh its myriad benefits?

In this exploration of the intricate relationship between running and well-being, we navigate the terrain where the rhythmic cadence of each stride intersects with the delicate balance of health.

Endurance events are becoming increasingly popular. The demographic has changed in recent years to include a higher proportion of women and the average age of participants has also increased. Many of us are familiar with the tale of the first marathon runner, Pheidippides, who ran from Marathon to Athens in 490 BC, and died suddenly after delivering his triumphant message of victory in battle. Pheidippides is widely acknowledged as the first documented sudden cardiac death in an endurance runner. Sudden cardiac death is a known risk for endurance runners, with a high proportion of deaths in marathons happening in the final mile and a higher risk in males. An emerging body of evidence suggests that the benefits of running lessen at the training levels required for marathon and ultra-marathon training. There is evidence of an increased risk of arrhythmias (predominantly atrial fibrillation), sudden cardiac death, hypertension and even coronary artery disease for those who participate in chronic endurance running training. However, placing this in context, the mortality rates for those engaging in endurance running training are still lower than for those who do not exercise.

Running is a dynamic and rewarding activity that can significantly contribute to heart health. Whether you’re a newcomer to the running scene or looking to reignite your passion for pounding the pavement, here are some benefits of running to help you begin your running journey and support cardiovascular well-being:

- Start Gradually: If you’re new to running or returning after a hiatus, begin with a manageable pace and distance. Gradual progression reduces the risk of injury and allows your cardiovascular system to adapt gradually.

- Establish a Routine: Consistency is key. Set a realistic schedule for your runs, whether it’s a few times a week or a daily commitment. A routine helps your body adjust and enhances the long-term benefits for your heart.

- Mix Walking and Running: Incorporate intervals of walking and running to build stamina and reduce the risk of overexertion. As your fitness improves, you can gradually increase the running segments.

- Invest in Proper Footwear: Quality running shoes provide support and cushioning, minimizing the impact on your joints and reducing the risk of injury. Visit a specialized store for a proper fitting to find the right pair for your feet and running style.

- Warm-Up and Cool Down: Prioritize warm-up exercises to prepare your muscles and joints for the activity. Likewise, cool down with stretches to improve flexibility and aid in recovery.

- Listen to Your Body: Pay attention to any signs of discomfort or pain. It’s normal to experience muscle soreness, but persistent pain may indicate an issue. Consult with a healthcare professional if needed.

- Set Realistic Goals: Establish achievable goals that align with your fitness level. Whether it’s running a certain distance, improving your pace, or participating in a local race, setting milestones keeps you motivated.

- Hydrate and Nourish: Staying hydrated is crucial for overall health, including cardiovascular function. Consume an adequate amount of water and maintain a balanced diet to improve the benefits of running.

- Cross-Train: Supplement your running routine with other forms of exercise, such as cycling or swimming. This helps prevent burnout, works different muscle groups, and enhances overall fitness.

- Listen to Your Heart: Monitor your heart rate during and after runs. This can provide valuable insights into your cardiovascular fitness. As your heart becomes more efficient, you may notice improvements in your resting heart rate.

Remember, the journey to heart health through running is personal and unique to each individual. Consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new exercise program, especially if you have pre-existing health conditions. With the right approach, running can be a fulfilling and heart-boosting endeavor for years to come.

The causes of the increased cardiac risks associated with chronic endurance training compared with less intense running are not well understood. “Athletes heart” is a well-known phenomenon – those who engage in high level sporting pursuits have larger heart chambers, thickened heart muscle, changes in resting heart rate and in the electrical conduction of the heart. Whether this is a beneficial adaptation to exercise or a maladaptive damaging process is up for debate. It is also known that there are temporary changes in heart function and increased levels of blood markers known to be associated with heart muscle damage shortly after completing marathon distance (or longer) events, which generally normalise within one week. What is less well understood is whether these short-term effects lead to long term changes, such as scarring of the heart muscle. How much running training is too much is a source of considerable debate.

The answer to this question is likely to be highly individual. For example, the risk of developing atrial fibrillation (a form of abnormal heart rhythm) appears to be highest in middle aged men who have participated for many years in endurance training and continue to compete at a master’s level. The risk is relatively low in young male athletes and risk for female endurance runners is much less well studied. The benefits of running for any individual depends on a variety of factors and running is not recommended for those with certain conditions, such as cardiomyopathy or severe aortic stenosis, as the risk profile is considered unacceptable. Many of us are simply unwilling to consider stopping long distance running training despite the perceived risk of endurance training because of its importance in our sense of physical and mental wellbeing. However there are some sensible steps that can be taken to mitigate risk – for example, a medical assessment prior to undertaking training for an endurance event (to produce a more personalised assessment of individual risk based on history, clinical examination and appropriate baseline investigations), stopping training and consulting a physician in the event of worrisome symptoms (including chest pain on exertion, palpitations or fainting symptoms, amongst others), incorporating appropriate rest periods into our training regimes and adopting cross-training to benefit from other forms of exercise.

In conclusion, running overall has excellent health benefits, both in terms of cardiovascular disease and general mortality risk. These advantages can be appreciated even with relatively low intensity and frequency running training. From a pure cardiovascular risk perspective, the cardiovascular health benefits of running are best in those training for shorter events, such as 5- and 10-kilometre races and lessen with increasing training volumes. At the extremes of endurance training, there are some increased risks which those who choose to participate in this type of event should consider and weigh up. If a person has a high risk personal or family history or has symptoms which may relate to running training, then they should consult a medical professional to determine the risk: benefit profile of continuing with this form of training.